Main Page

Most Recent News

Class Notes

Class Album

Things We've Done Index

In Memoriam

Facebook

Class Webmaster:

Mableton, GA

Phillips Exeter Academy Class of 1989

Things We've Done

(click above to return to list of contributing classmates)

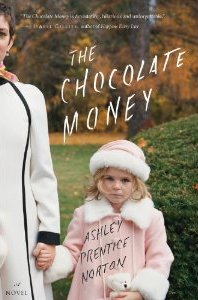

Ashley P. Norton

Excerpts from The Chocolate Money

(Published September 18, 2012. You can find it at Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble, and IndieBound. And yes, there's a Kindle edition)

I: Cardiss • II: Meredith

Bettina is the only child of Babs, a narcissistic chocolate heiress. Bettina does not know who her father is; for some reason Babs has kept it a secret. In this chapter, Bettina arrives as a new student at the boarding school, Cardiss Academy, after a summer in France with her mother’s cousin, Cécile.

Bettina is the only child of Babs, a narcissistic chocolate heiress. Bettina does not know who her father is; for some reason Babs has kept it a secret. In this chapter, Bettina arrives as a new student at the boarding school, Cardiss Academy, after a summer in France with her mother’s cousin, Cécile.

Cardiss

SEPTEMBER 9, 1983, is a bright, crisp day in Cardiss, New Hampshire. The leaves are green and sharp. The trees robust, sturdy, and tall. The sky has none of the dampness or gray tones one might expect to find across the pond in an English boarding school. I am fifteen when I arrive as a sophomore, or a Lower, in Cardiss-speak.

Cardiss presents the same front to everyone. It is beautiful in this way. It looks like a college, only smaller. The buildings are red brick. White marble steps with Latin sayings over the doorways. Lawns sprawl for the mere experience of sitting on them. Attractive boys and girls lounge, books and binders open, as if they were sunning themselves on an academic beach.

I don’t go back to Chicago before starting Cardiss. Babs says, It’s your deal, babe, you are too old for me to unpack your clothes, make your fucking bed. She has no interest in watery coffee, meeting all of the chipper parents who want to make small talk. She does buy me a silver-and-gold pen from Tiffany. Has it engraved with my initials. I plan to save it for exams. She also sends me a large check for tuition and airfare, and a wad of traveler’s checks to cover expenses for the whole year. It makes me feel independent. And sad.

After three months in France with Cécile, I fly directly from Paris to Boston. I take a cab to campus, about forty-five minutes away. Most new students arrive with their parents and I worry people will feel sorry for me, coming alone. Will wonder about the cab. But the driver takes me right to the front gates of campus and pulls away before anyone can notice.

I have one small bag. A Louis Vuitton duffel I bought on rue Georges V. Babs hates LV. Thinks it’s tacky to have logos stamped everywhere. Makes you look like you’re trying too hard to prove you can afford something expensive. But I like the bag. It’s completely incongruous with the things the other kids bring. Trunks filled with new sheets, down comforters, flannel PJs, stereos. My duffel, I hope, makes me look cool. Like I have purposely opted out of such teenage clutter. Chose to bring a few pants and tops from agnès b. and Petit Bateau because that’s what I like. But the truth is that I don’t have a clue what you’re supposed to wear at boarding school. I don’t know anything about the bluchers, rag socks, flannel pajamas that the others have. And I didn’t have the catalogs to order them from. I do bring the silver medallion of my father’s that Babs gave me. I have yet to try to find him, but maybe I will now that I am at Cardiss. Who knows. It will change things between me and Babs and I’m not sure I am ready for that.

I check out the map of campus that’s just past the front gate. I’m not assigned to a dorm but instead to a house called Bright. The idea is appealing: a small cluster of girls living in a real house with one female faculty member, generally a younger woman without a spouse or kids. Just starting her tenure at the school. The problem with the houses is that, unlike the dorms, they have a small number of students living in them, between four and six per house. Less margin for social errors.

Bright House is a two-minute walk from the front gate. I find it easily. It is white, two-storied, with black shutters. The front door is propped open. Just a screen door divides the inside from the outside. I walk into a living room that looks like it belongs in a tired B & B: dilapidated couches, worn shag carpeting, and a TV. There is a woman standing in the middle of the room tapping a clipboard with a pen and waiting for me.

She scribbles something on the paper attached to her clipboard. Looks about twenty-seven and has short brown hair. I know instantly (the rigid way she holds the clipboard?) that she will never have any children. She sports a khaki skirt, open-back clogs, and a pink-striped oxford shirt that has been ironed. She wears small crescent-shaped earrings. No makeup.

I expect her to smile but she approaches me briskly and sticks out her hand. Firm, businesslike.

“Bettina, you’re the last to arrive.”

It’s just after three. I thought we had all day to get there.

“Sorry,” I mumble.

“I’m Miss McSoren. Head of Bright House. I teach French. Coach field hockey.”

I want to like her, but I don’t. I know Miss McSoren has probably learned French at some all-women’s college and spent her junior year abroad in some provincial town like Rennes. I bet she can expertly navigate all of Molière and Camus but has never bothered with Paris Match, my favorite mag. I know Babs would laugh at her, and this makes me want to too.

One of my French teachers at Chicago Day, Madame Coutu, wore blouses so sheer we could see her nipples, the skin of her back. Our fifth-grade class was shocked and embarrassed. Babs was thrilled. Now that I am older, I can see what Babs was getting at. Can you really be a good French teacher if you have zip sex appeal?

“So, you’re from Chicago,” she says.

I’ve been too busy with my critical assessment to offer up any pleasantries. I smile, but again, I’m disappointed. I never know what people expect me to say to that. I don’t really consider myself from anywhere, at least nowhere anyone else lives. Babs is the country I come from. That’s the only way to explain it. I gather up my hair, which is now far past my shoulders, and tie it on top of my head in a knot. I nod and say, “Yes. And you?”

“Bangor,” she answers, but it’s clear from the clipped reply that I’m not supposed to be asking her personal questions. She gestures for me to follow her up the stairs.

“Your roommate, Holly, is already here. Dinner’s at six and we’ll be having a house meeting afterward, at eight. You still have some time to unpack.”

Holly, I know, is Holly Combs from Iowa City. There was a tiny index card in my acceptance packet with only this scant information about the girl I will be sharing a room with for the next nine months.

Miss McSoren talks over her shoulder as she climbs the stairs. Her bare legs are perfectly smooth and have the sheen of carefully applied lotion. I bet she shaves them on a schedule. Never nicks herself with the razor. Never has to scramble for toilet paper or Band-Aids to stop the bleeding. I have been using the same disposable razor for about six months and it never gets all the hairy patches. I just can’t keep up with my body.

We reach the landing. The door to bedroom number one is open. There’s a man in there, wearing khaki pants and a blue golf shirt. Must be Holly’s dad. He’s tightening the screws on the legs of her desk chair. He is large and mostly bald, working up a good sweat. A woman has her back to the door and is arranging things in a closet. Must be Holly’s mom. She hangs dresses with dresses, skirts with skirts, so that Holly can find things easily when she gets ready each day. She arranges clear stacking boxes that hold coiled belts, socks, tights, and hair accessories. I have never seen a couple working together on behalf of their child. Holly’s mom is about the same width as Holly’s dad. She has shoulder-length brown hair kinked from a perm. She turns when I reach the bed that is to be mine. She has already finished making up Holly’s. There’s a large blue dolphin on the comforter, and sheets with waves on them. I later find out Holly was a star on her swim team back home. In the middle of her pillow there is a ratty teddy bear wearing a T-shirt that says go hawkeyes!

Holly’s mom wears a pink pantsuit and white Keds. Opaque pink lipstick that makes her look like she has been eating Cray-Pas.

“Bettina!” she says with such friendliness that I am completely bewildered. She pulls me to her, and her body is big and soft, like a sofa. She is not shy about smothering me with it. Holds the back of my head and presses me even closer to her. I’m sure I will leave an imprint once she releases me.

“We have been waiting for you! What a wonderful time you girls will have!”

I look for Holly, who is nowhere to be seen. Holly’s mom looks around me as well. I, too, am missing a person.

“Where are your folks?” She says this in such a way that it’s obvious she has no doubt they will be along shortly. I just need to place them somewhere on Cardiss’s campus, attending to something else.

“I came by myself,” I say. Leave her to make up a reason why my parents aren’t there.

Holly’s mom eyes my solitary duffel. Sees the standard-issue sheets folded on my bed, grayish white with property of cardiss stamped on them. There are two maroon blankets next to the sheets that seem to promise all the comfort of burlap sacks. The LV bag does not register. For all she knows, I bought it at Kmart. Given these facts, Holly’s mom makes a quick calculation. It’s the wrong one, but generous all the same.

“Oh, lots of students come by themselves. Airfare can be expensive; so is renting a car. We drove our own. I’m so relieved that we all have the same values. Holly didn’t know what kind of roommate she would get. There are so many students here who come from important families, and Holly was worried she wouldn’t fit in. I said that everyone was just here to get an education, that having money or not doesn’t matter in the end. That there is just too much work for people to care about things like that. But I must say, I am more than a little relieved that you are from the Midwest too.”

It’s funny the way she says it. Like the Midwest is a small town where no one has any real money and everyone gets along. I nod in reply, though it is completely untrue. But I am certainly not going to bring up the chocolate money. Only Babs can be a fucking chocolate heiress with impunity. It would be social suicide for me to bring it up.

Holly’s dad stands up from his crouch by the chair. He strides over, pumps my hand.

“Tell her, Donna.”

“What?”

“What Holly thought about Bettina.”

“Oh, no, Dennis, it’s stupid.”

“No, it’s really funny if you think about it.”

I look at both of them: open faces, shining. Wait.

“When we got the card with your name on it, Holly thought you were related to Ballentyne chocolate. That you must have pots of money and live in a fancy apartment.” Donna starts to laugh.

Her presumption pisses me off. It’s true, of course, but it’s my secret to tell. It is not a really funny one, no matter how you think about it.

“I told Holly she would be lucky because your family would probably send you big care packages of chocolate. Chocolate is Holly’s favorite food. I make brownies every Sunday night, and by Tuesday morning, they’re always all gone.”

“Not true!” I turn to see Holly standing in a peach robe, her long brown hair dripping wet. She wears teal flip-flops and carries a metal bucket that holds all her bathroom amenities. She’s beautiful. I can’t believe she left her parents unattended. Trusted them to be alone with her things. Make first impressions on the people who will make or break her Cardiss experience.

“My favorite food is ice cream, then chocolate!” She laughs. I see her wet hair making small puddles on our wooden floor. She is shorter than I am, probably five four to my five seven, but she looks more developed. She has boobs and hips, while I do not. I’ve gotten my period, but I have yet to achieve a woman’s body. My puberty fat has not distributed itself into come-hither sexy parts. It’s as if my hormones have gone on strike.

Holly’s eyes are brown, like her hair. There is a lightness and sweetness in them that makes them pretty. She looks wholesome, pastoral. Like a character in a Hardy novel but no one I have ever seen in real life. She’s near enough that I can smell her shampoo. It has a fruitiness to it. Probably some variation of Herbal Essence that comes in a pink or green bottle with complementing conditioner. In France, you buy shampoo at the pharmacy. It’s so expensive you are only supposed to use it once or twice a week. I hardly even bother to do that. Instead, I wear a heavy mist of Coco perfume, and with my smoking, I never achieve Clean.

“As for the brownies, Jenny helps.” Holly puts the bucket with her bathroom things on top of her dresser. Begins toweling off her hair. Her towel is white with pink trim, and I can tell by the crisp white color and the way the threads are not matted together that it is new. Bought especially for her Cardiss experience. A reminder from her parents that she hasn’t been sent away for good. When she comes home to Iowa City, all of her old things, towels and sheets included, will be waiting for her.

I look at Holly and try to initiate a casual conversation even though we have not yet been introduced. I’m still pretty dismal when it comes to making friends with girls my own age.

“Is Jenny your sister?”

“Best friend,” Holly and her mom say in unison, then laugh at their synchronicity.

“Jenny and Holly have been best friends since kindergarten,” Donna continues. “I’m really surprised she didn’t sneak into the car with us. Holly has already written her twice since we left.”

I picture big bubbly writing and envelopes with stickers. Purple ink.

“Holly is going to bankrupt us with all that postage.”

“Mommy, stop! You keep blabbing on about me like I am not here.”

Mommy? Is she fucking kidding? I have taken to swearing, speaking Babs. At my age, it is not clumsy, awkwardly precocious. Instead, it gives me an edge.

But I can’t be completely cynical about Holly’s Mommy. I still don’t even get to say Mom when referring to mine. Suddenly I feel like I have been cruelly tricked. I thought the whole point of boarding school was that there were no parents.

Holly walks over. Gives me a hug. I’m somewhat stunned but hug her back. Her robe is damp, but her body is still warm from the shower. I want to put my head on her shoulder, let it stay there. I am so tired. But I pull myself away. Sit down on my bed. I want, need, a cigarette but know Holly and her mommy will be horrified if I light up in the dorm room. This is probably one of the best thing about Babs. If she were here, I would go right ahead. She would join me and later we would laugh at this earnest family from Iowa.

Holly doesn’t seem to notice my change in mood. She confidently walks over and grabs my hand.

“Bettina, I’m so excited we are going to room together! It’s going to be the best!”

I add exclamation points and double underlines to my growing list of her epistolary faux pas with Jenny.

“Mom, let’s give her the present!” Holly points to her closet.

Holly’s mom winks and digs in the back of Holly clothes. Hands me a fat cardboard tube with a red bow. I go from being disdainful to completely ashamed. It never even occurred to me to bring something for Holly. That’s my girl, self-absorbed as usual. But it’s not like we’re at a birthday party. It’s the first day of school. Not standard practice, as far as I know, to bring a gift. Still, I could’ve easily bought something, anything, from the duty-free at Charles de Gaulle. A mini Eiffel Tower? A pack of cards? But these people don’t even know I spend my summers in France. Have the chocolate money to travel outside Illinois. Didn’t come by Greyhound to Boston but flew internationally and then took an eighty-dollar cab ride to get to school. But Jenny would have brought a gift, I know.

I undo the package. It is a three-by-five-foot hook rug in Cardiss colors, a big gray B for Bettina, I presume, rising from a background of maroon threads.

“Thank you,” I say with as much enthusiasm as I can muster. I’m not exactly sure what the fuck it is or what I am supposed to do with it.

Holly whips one out from another tube. It has a gray H on it.

“Aren’t they great? My mom made them herself.” She puts hers down on the floor beside her bed. “So our feet won’t get cold in the morning.”

I kneel and follow her lead.

“See, it’s just like being in a hotel!” she adds.

More like a Barbie House, if Barbie lived in a ranch and made her own curtains, I think. But really, I’m touched.

“They are great,” I say slowly. “Thank you,” I add again, inanely. “I’m sorry, I didn’t...”

Holly’s mom grabs my shoulder. “Don’t you worry, my dear. We had fun doing it! Two are just as easy to make as one. What’s important is that you girls stick together. It’s going to be a lot of work this year, and I know there will be some richies who won’t be nice like you are. You’re going to need each other.”

Holly’s dad comes over to us and takes out his wallet. He pulls out two ten-dollar bills. Gives one to Holly and one to me.

I am mortified. Try not to take it. Shake my head and wave it away.

“Now, Bettina, this is nothing,” he says. “Just a little money so you can get a poster for the wall by your desk, and maybe some snacks at the Cardiss Grill.” He takes my hand and puts the money into it. No way I can give it back.

I have three thousand dollars in AmEx traveler’s checks stuck in the Marie Claire in my duffel. I know Holly will find out about the chocolate money eventually, and then she and her parents will hate me for taking theirs. But I can’t think of a way to explain this to them. Say no. I decide to just take the ten dollars and give it back at a later point. Maybe when her parents leave, I’ll just tell Holly I can’t accept it. It’s way too much. Or I could use it to buy her something, the present I didn’t think to arrive with.

I set the money down on the empty wooden desk that is to be mine and say, “Thank you very much.” They all look at me strangely, and I realize I’ve made another mistake. I’m supposed to put it in my pocket or safely tuck it in a wallet. Normal people don’t leave money lying around.

I quickly pick up the ten and stuff it in my duffel. I will not unpack the things I’ve brought until Holly’s parents have left. Bonjour tristesse, an ashtray in the shape of Sacré-Coeur, a carton of Marlboro Reds. The green bomber jacket I bought myself from a shop near the Sorbonne, the kind all the French students wear. I’m sure my strange foreign things will make them want to take back the hooked rug.

An hour later, when Mr. and Mrs. Combs are ready to leave, Holly and I walk down with them to their car. The green Jeep Cherokee has some dents in it and there are crumbs on the floor. In the back seat, the September issues of Glamour, Seventeen. Holly’s dad gives her a big hug and goes to work unlocking the door. Holly’s mom fishes in her bag, rooting through keys, breath mints, loose change, and lipstick to pull out a small pack of Kleenex. She puts her hand on the back of Holly’s neck and pulls her close. They touch foreheads. An alternative form of kissing, I suppose, a mark of togetherness. Holly’s a part of her mom. First a tender plan, then a girl birthed and cared for.

Holly starts laughing and crying. She grabs her mom around the waist and puts her face on her shoulder. Holly’s mom’s chin quivers and she dabs at her eyes with a small rectangle of folded Kleenex. At first, I feel the tiniest bit of contempt. I’ve never cried when saying goodbye to Babs. Not even when I was five and went to France for the summer for the first time. I thought I was just brave, more mature than other kids. Now I know it was because there was nobody to cry back.

I’d wanted to avoid this scene. Stay in the house and smoke a cigarette, but Holly’s parents insisted I come. They want a picture of the two of us in front of Bright House. Roomies on our first day of Cardiss. They will develop the film when they get home and put the picture on their fridge. Or Holly’s mom might even have it printed on a mug and take it to work with her, to whatever stupid job she spends her day doing. Holly and her mom break their embrace, both still crying and laughing. Holly grabs my hand, and we strike a pose against the door of Bright House.

Holly is wearing jeans and a maroon Cardiss sweatshirt with a hood. Her feet are still bare. It is almost five, but the sky is still light as day. I am wearing the gray agnès b. T-shirt and black linen pants with black Converse low-tops that I pulled on over twenty-four hours ago. As Holly’s mom works to focus the camera, I realize I do want to be in this picture after all. I have never kept a friend for more than a year, but this beginning suddenly seems promising. Perhaps because it’s stripped of Babs, I have just a little bit of faith in it.

Holly puts her arm around my shoulder. Her parents seem a bit too friendly, but I remind myself that the Combses would’ve acted this way with whoever turned out to be Holly’s roommate. They’re just trying to provide Holly with some sort of insurance that her year will go well.

I feel very, very tired. I didn’t sleep on the flight and have now been awake for almost two days. I smile for the picture, but it is all I can do to return their hugs goodbye. Some small part of me wishes that if I went back up to my room I’d find Babs there. Making up my bed with sheets she bought from Marshall Field’s. Adorning my desk with a real leather blotter and pencil cup. Babs loves an opportunity to shop, and I can’t believe that she has passed this one up.

The Chocolate Money was published on September 18, 2012. It is available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and IndieBound. Yes, there is a Kindle edition. Be sure to check out Ashley's primary presence on the web at www.ashleyprenticenorton.com.

All content on this site is maintained by members

of the Class.

Lion

Rampant and Academy

Seal © Copyright The Trustees of Phillips

Exeter Academy.

Questions? Contact the

.

Updated

Wednesday, January 16, 2013 4:21 PM

Eastern Time.